Bit Shift Operator

Table of Contents

Intro

When I was learning how to code in C, I came across an operator called the bit shift operator. The concept was so simple — it just shifts the bits in the binary representation based on the direction and the number of bits to shift. But when I was learning, I didn’t notice some of the catches and the beautiful ways computers handle these operators.

Later, when I was reading about the x86 architecture, I came across these operators again. The book1 I was referring to had only one paragraph about them, but I wanted to know more — what was happening deep down inside the tiny world of x86 architecture? How is bit shifting handled for different data types? Why does it work faster than multiplication and division in certain cases?

There are only two prerequisites for this blog:

- A willingness to understand things.

- Some programming background.

Note: Obviously, I can’t explain everything, lol — you’ll have to Google some stuff on your own!

What is Bit Shift in C

Okay, let’s get started with our blog , which is a deep dive into bit shift operators.

What are Bit Shifts?

As the name suggests, bit shifting simply means shifting bits in a binary representation. There’s nothing much to it, lol! The real magic lies in how the assembly decides how to shift those bits based on different data types.

In short, you can say there are two types of bit shifts:

Right shift

Left shift

The syntax for right shift in C is as follows:

a >> 1

This code shifts the bits of the variable a by one position to the right. What does that mean? Let’s take a simple example.

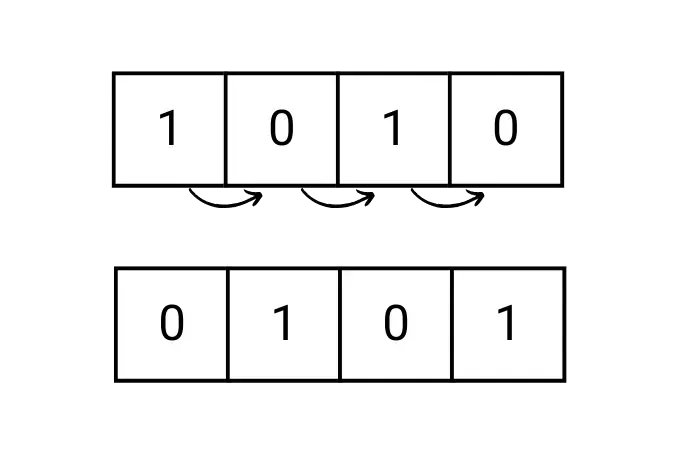

Say a has this binary representation: 0b1010. This is the binary for 10 (0b is just a convention to indicate it’s a binary representation). When a right shift is done:

0b1010

0b0101

The bits move one position to the right. Below is a simple img with arrows showing the shift.

One interesting thing here is that after the right shift, a 0 came into the MSB (most significant bit, i.e., the extreme left). How was that determined? What if instead of int, it was a signed int or a char? What would have happened? We’ll get into that deeper later in this same blog.

Another thing to note is that after the right shift, the resulting binary is 0101, which is 5! Did you notice this? When you right shift, the bits move to the right, and the number gets divided by two! (Not always—there’s a catch, which we’ll discuss soon.)

Why does this happen?

(Think about it! 😎 It’s something to do with how binary representation works and how decimal numbers are represented in binary notation.)

For left shift, everything is similar. For normal integers, the bits shift to the left, and instead of dividing, the number gets doubled! 😲

For now, let’s just look at how bit shifting affects different data types. Below, I’ll list examples for various types using this format:

Data Type: <type>

Original Value: <value>

Original Binary: <binary>

Right Shift (>> 1): <value> | <binary>

Left Shift (<< 1): <value> | <binary>

Examples

=== Bit Shift Demo ===

Data Type: signed char

Original Value: -10

Original Binary: 11110110

Right Shift (>> 1): -5 | 11111011

Left Shift (<< 1): -20 | 11101100

Data Type: signed short

Original Value: -1000

Original Binary: 11111100 00011000

Right Shift (>> 1): -500 | 11111110 00001100

Left Shift (<< 1): -2000 | 11111000 00110000

Data Type: signed int

Original Value: -100000

Original Binary: 11111111 11111110 01111001 01100000

Right Shift (>> 1): -50000 | 11111111 11111111 00111100 10110000

Left Shift (<< 1): -200000 | 11111111 11111100 11110010 11000000

Data Type: signed long

Original Value: -1000000000

Original Binary: 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11000100 01100101 00110110 00000000

Right Shift (>> 1): -500000000 | 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11100010 00110010 10011011 00000000

Left Shift (<< 1): -2000000000 | 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 10001000 11001010 01101100 00000000

Data Type: signed long long

Original Value: -9000000000000000000

Original Binary: 10000011 00011001 10010011 10101111 00011101 01111100 00000000 00000000

Right Shift (>> 1): -4500000000000000000 | 11000001 10001100 11001001 11010111 10001110 10111110 00000000 00000000

Left Shift (<< 1): 446744073709551616 | 00000110 00110011 00100111 01011110 00111010 11111000 00000000 00000000

Data Type: unsigned char

Original Value: 100

Original Binary: 01100100

Right Shift (>> 1): 50 | 00110010

Left Shift (<< 1): 200 | 11001000

Data Type: unsigned short

Original Value: 10000

Original Binary: 00100111 00010000

Right Shift (>> 1): 5000 | 00010011 10001000

Left Shift (<< 1): 20000 | 01001110 00100000

Data Type: unsigned int

Original Value: 3000000000

Original Binary: 10110010 11010000 01011110 00000000

Right Shift (>> 1): 1500000000 | 01011001 01101000 00101111 00000000

Left Shift (<< 1): 1705032704 | 01100101 10100000 10111100 00000000

Data Type: unsigned long

Original Value: 4000000000000

Original Binary: 00000000 00000000 00000011 10100011 01010010 10010100 01000000 00000000

Right Shift (>> 1): 2000000000000 | 00000000 00000000 00000001 11010001 10101001 01001010 00100000 00000000

Left Shift (<< 1): 8000000000000 | 00000000 00000000 00000111 01000110 10100101 00101000 10000000 00000000

Data Type: unsigned long long

Original Value: -446744073709551616

Original Binary: 11111001 11001100 11011000 10100001 11000101 00001000 00000000 00000000

Right Shift (>> 1): 9000000000000000000 | 01111100 11100110 01101100 01010000 11100010 10000100 00000000 00000000

Left Shift (<< 1): -893488147419103232 | 11110011 10011001 10110001 01000011 10001010 00010000 00000000 00000000

Data Type: enum TestEnum

Original Value: 5

Original Binary: 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000101

Right Shift (>> 1): 2 | 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000010

Left Shift (<< 1): 10 | 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001010

Data Type: _Bool

Original Value: 1

Original Binary: 00000001

Right Shift (>> 1): 0 | 00000000

Left Shift (<< 1): 2 | 00000010

Observations

After reading the examples above, you must have noticed something 👀 — bit shifting behaves differently for signed and unsigned data types! We’ll dive into those differences and the “gotchas” in the next section of this blog.

Now, you might ask yourself: Why should I use this? Why would I move bits in a number from left to right or right to left? I don’t see any use for this in my life — let’s exit this blog!

Hold up, bro! You’re doing it wrong. Bit shifting helps certain computations in a program be carried out faster. For example, if a program takes 10 CPU cycles to complete a task (a cycle is the basic unit that measures a CPU’s speed), bit shifting can perform that same complex task in fewer than 10 cycles!

Signed vs Unsigned Bit Shifts (Deep Dive)

Until now, we saw what bit shifts are and looked at some interesting examples across different data types. In this blog, we’ll uncover why signed and unsigned bit shifts look different, like we noticed earlier.

Right Shift — The Problematic One!

Let’s first explore right shift, because that’s where things get tricky.

For unsigned numbers, if you right shift, a 0 is added at the MSB (most significant bit). Let’s see this with an example:

unsigned int a = 10;

a = a >> 1; // right shift by one bit

printf("%d", a);

The output of this snippet will be:

5

At the bit level, a = 10 is represented as:

00000000 00000000 00000000 00001010

After right shift by one bit, it becomes:

00000000 00000000 00000000 00000101

If you calculate the value of this binary, it is indeed 5. So this works exactly as expected!

Did You Notice This Peculiar Thing? 👀

Up until now, did you notice something weird about bit shifting?

If you did, you’re a clever reader — you don’t just read and let it go!

If you didn’t, don’t worry, I’m like you — I’ll tell you!

When we bit shift to the left, the number gets multiplied by 2!

When we bit shift to the right, the number gets divided by 2! 🔥

This is a characteristic of how bit shifting works and how binary representation operates. When bits are shifted, powers of 2 are either added or removed, which explains this behavior.

There are edge cases too, but we’ll get to those later in this same blog. For now, just keep this in mind so we can go deeper.

Right Shift for Signed Integers — Let’s Do It by Hand!

Now, let’s see what happens when we right shift a signed integer. We’ll go through it manually (or with a calculator, maybe).

Let’s take this example:

int a = -10;

The binary representation of a = -10 is as follows:

Step 1: Forget the sign

a = 10

binary = 1010

32-bit representation = 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001010

Step 2: Take 2’s complement (flip the bits and add 1)

Flip bits:

11111111 11111111 11111111 11110101

Add 1:

+ 1

-----------------------------------

11111111 11111111 11111111 11110110

So this is how -10 is stored in memory!

Now, what if we naively right shift it like we did with unsigned numbers?

01111111 11111111 11111111 11111011

Notice the MSB is now 0, so the sign is lost! That’s not what we want.

If we interpret this as a number, it’s 2147483643, but we expected -5. All the problem arose because we replaced the sign bit with 0 — everything got messed up!

What does the computer actually do?

Instead of inserting 0, it preserves the sign by inserting 1 at the MSB:

11111111 11111111 11111111 11111101

This is the correct representation of -5! 🎉

This works because in 2’s complement, the MSB represents the sign. If we replace it with 0, the meaning of the number changes completely! So, by keeping the MSB as 1, the computer preserves the sign and gives the correct result.

Think About It!

When you right shift -10, you’re essentially dividing it by 2. If the computer treated it as unsigned and inserted a 0 at the MSB, it would suddenly look like a huge positive number — totally breaking the logic!

Preserving the sign ensures that the operation makes sense and gives the expected output.

Left Shift for Signed Integers — Let’s Explore!

Now that we understand right shift, let’s uncover the mysteries of signed left shift.

Let’s jump directly into an interesting example:

signed char a = -10;

a = a << 1; // left shift by one bit

printf("%d", a);

Here, we’re using signed char, which is basically an 8-bit integer because characters are ultimately mapped to numbers.

Binary Representation

The binary representation of a will be:

11110110

What Happens Next?

In C, when we left shift a signed number, it first gets promoted to 32 bits, like this:

11111111 11111111 11111111 11110110

After promotion, the bit shifting is carried out normally, ignoring overflow bits:

11111111 11111111 11111111 111101100

And the decimal equivalent of this is -20.

So once again, we see that when left shifting, the number is multiplied by 2!

Bit shifting Across Datatypes

Now that we’ve seen the main point where people get confused — why bit shifting behaves differently for signed and unsigned values — let’s explore how bit shifting works with different datatypes. Each behaves slightly differently depending on its size, representation, and rules. Let’s deep dive into them one by one!

Integer Types (signed + unsigned)

char

Size: 1 byte

Storage capacity: 256 values with 1 byte

Signed range: -128 to 127

Unsigned range: 0 to 255

Example – 1:

Before bit shifting (decimal and binary):

unsigned char ch = 14; // Binary: 0b00001100

signed char sch = -20; // Binary: 0b10111100

After left shift:

ch = 28; // Binary: 0b00011000

sch = -40; // Binary: 0b11111111111111111111111111011000 // Promoted to 32-bit

chsimply doubles after left shift.schpreserves its sign while shifting!

After right shift:

ch = 7; // Binary: 0b00000110

sch = -10; // Binary: 0b11011110

chhalves after right shift.schpreserves its sign.

short

Size: 2 bytes

Storage capacity: 65,536 values

Signed range: -32,768 to 32,767

Unsigned range: 0 to 65,535

Example – 1:

Before bit shifting:

unsigned short ch = 14; // Binary: 0b0000000000001110

signed short sch = -20; // Binary: 0b1111111110111100

After left shift:

ch = 28; // Binary: 0b0000000000011100

sch = -40; // Binary: 0b11111111111111111111111111011000

chdoubles normally.schpreserves sign during shift.

After right shift:

ch = 7; // Binary: 0b0000000000000111

sch = -10; // Binary: 0b11111111111111111111111111110110

chhalves normally.schpreserves sign.

int

Size: 4 bytes

Storage capacity: 2³² values

Signed range: -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647

Unsigned range: 0 to 4,294,967,295

Example – 1:

Before bit shifting:

unsigned int ch = 14; // Binary: 0b00000000000000000000000000001110

signed int sch = -20; // Binary: 0b11111111111111111111111111101100

After left shift:

ch = 28; // Binary: 0b00000000000000000000000000011100

sch = -40; // Binary: 0b11111111111111111111111111011000

chdoubles as expected.schpreserves sign using arithmetic shift.

After right shift:

ch = 7; // Binary: 0b00000000000000000000000000000111

sch = -10; // Binary: 0b11111111111111111111111111110110

chhalves.schpreserves sign during shift.

long (on 64-bit systems)

Size: 8 bytes

Storage capacity: 2⁶⁴ values

Signed range: -9,223,372,036,854,775,808 to 9,223,372,036,854,775,807

Unsigned range: 0 to 18,446,744,073,709,551,615

Example – 1:

Before bit shifting:

unsigned long ch = 14; // Binary: 0b...00001110

signed long sch = -20; // Binary: 0b...11101100

After left shift:

ch = 28; // Binary: 0b...00011100

sch = -40; // Binary: 0b...1111011000

chdoubles normally.schpreserves sign during shift.

After right shift:

ch = 7; // Binary: 0b...00000111

sch = -10; // Binary: 0b...1111110110

chhalves.schuses sign extension.

long long

Size: 8 bytes

Same behavior as

longon most systems.

Example – 1:

Before bit shifting:

unsigned long long ch = 14;

signed long long sch = -20;

After left shift:

ch = 28;

sch = -40;

After right shift:

ch = 7;

sch = -10;

chdoubles normally.schpreserves sign extension.

_Bool

Size: 1 byte (aligned in memory, even though only one bit is meaningful)

Values: 0 (false) or 1 (true)

Shifting behavior:

Allowed, but doesn’t really make sense.

Any shift operation first promotes it to

int.

Example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

_Bool b = 1; // True

printf("%d\n", b << 1); // Output: 2

printf("%d\n", b >> 1); // Output: 0

return 0;

}

- Left shift promotes

_Booltointand doubles it. - Right shift shifts out the only bit, resulting in

0.

enum

Size: Same as

intby defaultShifting behavior:

Works like shifting

int.Can produce invalid enum states!

Example:

#include <stdio.h>

enum Color { RED = 1, GREEN = 2, BLUE = 4 };

int main() {

enum Color c = RED;

printf("%d\n", c << 1); // Output: 2 (GREEN)

printf("%d\n", c >> 1); // Output: 0 (invalid state)

return 0;

}

RED << 1becomes2, matchingGREEN.RED >> 1becomes0, invalid as an enum but valid as an integer.

Floating Point Types

Bitshifting of floating point not allowed !!

float

Size: 4 bytes

Range: ±3.4 × 10³⁸

Representation: IEEE 754

1 bit for sign

8 bits for exponent

23 bits for mantissa

double

Size: 8 bytes

Range: ±1.7 × 10³⁰⁸

Representation: IEEE 754

1 bit for sign

11 bits for exponent

52 bits for mantissa

Why shifting is invalid in floats and doubles

They are not stored as plain integers — they follow the IEEE 754 format.

Trying to shift a

floatordoubledirectly will either throw a compiler error or cause undefined behavior.

Example of invalid code:

float f = 3.14;

printf("%d\n", f << 1); // Invalid operands error

Where are these used ?

Okay, now you know a lot about bit shifting, its edge cases, and how it behaves for signed and unsigned values. But why do all this? What’s the point of learning these operations? Why emphasize them so much? Why even write this blog? Let’s get into the crux of the matter!

For simplicity, let’s stick to the int datatype and the x86_64 architecture. I’m compiling all codes using gcc 11 on Ubuntu 24.04 LTS. Also, I’ll maintain a GitHub repo and share the link so you can check out the programs2 for yourself.

Multiplying by 8

Let’s consider a simple program with one function that takes a number and returns 8 times the number!

#include <stdio.h>

int multiplyby8(int a) {

return a * 8;

}

int main() {

int a = 12;

int b = multiplyby8(a);

printf("%d\n", b);

return 0;

}

I compiled this code3 with the following command:

gcc -o main main.c

When I ran it, it gave the expected output 96.

But this isn’t the highlight! The real magic happens when we inspect the assembly output.

Inspecting Assembly Output

I created a disassembly of the binary like this:

objdump -d main > mult8dump.txt

Then opened it with my favorite text editor (mine is vim), and found a lot of x86_64 jargon! Don’t worry if you feel overwhelmed — stick with me. 💪🏼

Key Observations

Let’s focus on the multiplyby8 function and main. Below is the relevant assembly dump:

115 0000000000001149 <multiplyby8>:

116 1149: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

117 114d: 55 push %rbp

118 114e: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

119 1151: 89 7d fc mov %edi,-0x4(%rbp)

120 1154: 8b 45 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

121 1157: c1 e0 03 shl $0x3,%eax

122 115a: 5d pop %rbp

123 115b: c3 ret

Understanding Line by Line

Line 116 (

endbr64) – A security feature from Intel called CET. Not relevant here, just something to note.Line 117 (

push %rbp) & Line 118 (mov %rsp,%rbp) – This is boilerplate that saves the previous stack frame and creates a new one for the function.Line 119 (

mov %edi,-0x4(%rbp)) – Moves the function argument into local storage.Line 120 (

mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax) – Moves that argument into theeaxregister.Line 121 (

shl $0x3,%eax) – This is the highlight! It shiftseaxleft by 3 bits, which is equivalent to multiplying by 23=82^3 = 8.Line 122 (

pop %rbp) & Line 123 (ret) – Restores the previous frame and returns.

The Real Insight

Even though we wrote:

return a * 8;

the compiler optimized this into a shift operation! Modern compilers reduce computational steps using clever techniques like bit shifting when possible.

Multiplying by 9?

What if we multiply by 9? Which is not 2’s power. Let’s look at the assembly output:

115 0000000000001149 <multiplyby9>:

116 1149: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

117 114d: 55 push %rbp

118 114e: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

119 1151: 89 7d fc mov %edi,-0x4(%rbp)

120 1154: 8b 55 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%edx

121 1157: 89 d0 mov %edx,%eax

122 1159: c1 e0 03 shl $0x3,%eax

123 115c: 01 d0 add %edx,%eax

124 115e: 5d pop %rbp

125 115f: c3 ret

Here’s what’s happening:

- It shifts

aleft by 3 (multiply by 8), then addsaonce to the result →8a + a = 9a.

Optimization again!

Multiplying by 13?

Let’s see what happens when we multiply by 13:

115 0000000000001149 <multiplyby13>:

116 1149: f3 0f 1e fa endbr64

117 114d: 55 push %rbp

118 114e: 48 89 e5 mov %rsp,%rbp

119 1151: 89 7d fc mov %edi,-0x4(%rbp)

120 1154: 8b 55 fc mov -0x4(%rbp),%edx

121 1157: 89 d0 mov %edx,%eax

122 1159: 01 c0 add %eax,%eax

123 115b: 01 d0 add %edx,%eax

124 115d: c1 e0 02 shl $0x2,%eax

125 1160: 01 d0 add %edx,%eax

126 1162: 5d pop %rbp

127 1163: c3 ret

Here’s what’s going on:

ais doubled →2aais added →2a + a = 3aShift left by 2 →

3a × 4 = 12aAdd

aagain →12a + a = 13a

Even when it’s not a power of two, the compiler finds ways to optimize!

Why Learn This?

You might say, “But if the compiler is optimizing for me, why do I even need to know this?”

Well, it’s not about blindly trusting the compiler—it’s about understanding what it’s doing, when optimizations are applied, and how to write efficient, predictable, and maintainable code.

Here’s why it matters:

Embedded systems and hardware-level programming often run in environments where compilers can’t optimize everything.

In debug builds, optimizations might be disabled.

Understanding low-level operations helps you write algorithms that are faster and use fewer resources.

It helps you communicate intent clearly and troubleshoot performance issues.

You become a programmer who understands how code works at its core—not someone who blindly trusts tools.

Mastering these techniques makes you a better programmer, not just someone who lets compilers do the work.

Edge Cases in Bit shifting.

Okay now that we know how bit shifting works and how it’s used by compilers to optimize code, let’s talk about the dark corners — the edge cases. These are situations where things don’t behave as expected, or worse, produce bugs, undefined behavior, or platform-dependent results. Knowing these will not only help you avoid mistakes but also understand when the compiler or hardware might not be able to save you!

Let’s go through them one by one. We’ll keep it simple and mostly stick to int or other common types unless explicitly needed.

Left shifting into or past the sign bit (overflow)

This is one of the biggest edge cases that trips people up!

Scenario:

int a = INT_MAX; // 0x7FFFFFFF -> 01111111 11111111 11111111 11111111

a = a << 1;

What happens:

INT_MAXis the largest positive integer that can be stored in a signed 32-bitint.It’s

0x7FFFFFFF→01111111 11111111 11111111 11111111.Left shifting by 1 pushes out the leftmost bit and introduces a

0at the rightmost bit →11111111 11111111 11111111 11111110.Now the sign bit is

1, meaning it’s a negative number → this is undefined behavior in C for signed integers!

Why it’s dangerous:

Some compilers may wrap around, some may signal an error, some may leave garbage data.

Arithmetic shifts don’t apply — it’s about storage overflow and the C standard doesn’t guarantee the outcome.

Right shifting negative numbers (sign extension vs zero fill)

We briefly discussed this before, but it’s worth revisiting.

Scenario:

int a = -4; // 0xFFFFFFFC -> 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111100

a = a >> 1;

What happens:

Arithmetic right shift fills the new leftmost bits with the original sign bit.

So

11111111 11111111 11111111 11111100becomes11111111 11111111 11111111 11111110.This is still

-2, which makes sense for division by 2.

Edge case:

Implementation-defined:

The C standard allows compilers to decide whether the sign bit is preserved or not. Some platforms might zero-fill the leftmost bits!Always be cautious — behavior might vary across architectures.

Right shifting beyond or equal to the width of the type

Scenario:

int a = 1;

a = a >> 32;

What happens:

For a 32-bit

int, shifting by 32 or more is undefined behavior!The CPU might mask the shift count or result in unpredictable behavior.

Lesson:

- Always ensure that the shift count is less than the number of bits in the type (

0through31forint).

Left shifting zero or one into overflow territory

Scenario:

int a = 1;

a = a << 31;

What happens:

Left shifting

1by 31 positions sets the sign bit →0x80000000.Some systems interpret this as

INT_MIN(-2147483648).Still defined because it’s exactly on the boundary, but further shifting would be undefined.

Shifting negative signed values in left shifts

Scenario:

int a = -1;

a = a << 1;

What happens:

The result is undefined behavior because the sign bit is overwritten unpredictably.

Some architectures may perform it like unsigned shifting, some may generate incorrect results.

Mixing signed and unsigned types

Scenario:

unsigned int a = 1;

int b = -1;

int result = a << b;

What happens:

The shift count

bis negative → undefined behavior.Even if

bwere positive, mixing signed and unsigned can cause implicit conversions leading to surprises.

Lesson:

- Always ensure both the shift operand and the shift amount are clearly defined.

Final Notes

Edge cases in bit shifting are where things go from predictable and neat to unpredictable and dangerous. Understanding how sign bits are handled, how overflow is treated, how compilers and hardware differ, and how type promotions work are crucial when writing efficient and bug-free code.

Summary

Alright guys, now that we’ve gone through all these sections from 0.0 to 0.5, let’s quickly recap what we’ve learned so far!

We started by understanding what bit shifting is, how simple it looks at first, but how deep it actually goes when you start thinking about binary, architecture, and how computers process data.

Then we uncovered the difference between signed and unsigned shifts — especially how the sign bit matters when shifting and why preserving it is necessary to avoid breaking logic.

We explored how bit shifting behaves across different datatypes, like

char,short,int,long,long long,_Bool, andenum. You saw how each one is stored in memory, how shifting works on them, and what kind of results you can expect.We dove into why bit shifting even matters, by inspecting how compilers optimize code and use shifting to perform faster multiplication or division operations. The assembly examples showed exactly what the compiler does behind the scenes!

Finally, in this section on edge cases, we learned about situations where things can go wrong — like shifting into the sign bit, overflowing, mixing signed and unsigned types, or right shifting negative numbers. These are the traps that can mess up your program if you’re not careful.

These foundations are crucial if you want to not only write efficient code but also understand how your code behaves under the hood. We’ve only scratched the surface, and in upcoming blogs we’ll explore more such topics, read some more assembly

Thank you for reading, stay tuned for upcoming blogs.

Deep Dive into Systems ↩︎